Sentiment classification is somewhat of a trend in NLP; it consists of classifying small texts according to its sentiment connotation: a positive or negative feeling. Today we’ll use the Sentiment140 dataset to train a classifier model in python. The dataset consists of 1.6 million sentiment-labeled tweets. The encoding must be manually set.

import re

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

from matplotlib import pyplot as plt

data = pd.read_csv('training.1600000.processed.noemoticon.csv', encoding = 'ISO-8859-1', header = None)

data.columns = ['sentiment','id','date','flag','user','tweet']Let’s take a look at some tweet examples by sentiment:

from random import sample

data_positive = data.loc[data['sentiment'] == 4]

pd.options.display.max_colwidth = 200

data_positive.iloc[sample(range(len(data_positive)), 10)]['tweet']Flickr is uploading… Oooh, and these pics count towards my 101 things!

@mrdirector09 That’s why you have me

@michaelgrainger lmao! I understand bro…trust me

@kyleandjackieo I.e. I don’t need to know when you’re getting a coffee, and I don’t need to know all your deep thoughts about everything.

At sushi land

just realized my birthday isnt that far away a month and 3 days

@uhhitsangelaa thats good. glad ur feeling better girl!

@mikecane Thanks, Mike!

i just found out that my name means god’s grace in hebrew.

@rahnocerous tired. yr 12 is killing me, albeit slowly. 2 days left and im on 2 week break though

from random import sample

data_negative = data.loc[data['sentiment'] == 0]

pd.options.display.max_colwidth = 200

data_negative.iloc[sample(range(len(data_positive)), 10)]['tweet']The weather is blowing mines right now and I’m in traffic

@keza34 oh i havent, ive bn sat at home with withdrawels, so not good

Only powder pink slipon vans would have completed this look. I rushed out and forgot my hair ties

@jenleighbarry Hey Jen! Sadly no.. guessing you are!? Awsomeness! Can hear the click-click of your focused eye going to work!

Home. Don’t think i’ll wake up at 5. :-p I had set an alarm for 6 in the kids’ room & forgot to turn it off. I feel bad about that.

i woke up earlier than i wanted to thanks to Prince parade todayy

@janiceromero same thing happened to me.. it either you not use Akismet or just check your comments daily.

ok…am i java rookie…i knw…bt i hope ds openCMS docs make some sense

@clara018 yeah! my day seemed to pass so fast without him update

@cloverdash He’s playing Juan Ignacio Chela…who’s good on clay. very annoying. Fingers crossed though!

We can see that not all tweets are obviously positive or negative, the less obvious ones will be a challenge to our classifier.

Pre-Processing

Pre-processing is a huge step in our analysis, as it directly influences the model’s performance. We’ll use python regex to indicate words that are all caps, replace URLs for URL, user mentions with USER, remove all special symbols, indicate punctuation repetitions with REPEAT, hashtags with HASHTAG and word end elongations (e.g. heeyyyyyyy) with ELONG. English contractions are split, extra spaces removed and, finally, everything is set to lower case.

def preprocess_tweets(tweet):

#Detect ALLCAPS words

tweet = re.sub(r"([A-Z]+\s?[A-Z]+[^a-z0-9\W]\b)", r"\1 <ALLCAPS> ", tweet)

#Remove URLs

tweet = re.sub('((www\.[^\s]+)|(https?://[^\s]+))','<URL> ', tweet)

#Separate words that are joined by / (e.g. black/brown)

tweet = re.sub(r"/"," / ", tweet)

#Remove user mentions

tweet = re.sub('@[^\s]+', "<USER>", tweet)

#Remove all special symbols

tweet = re.sub('[^A-Za-z0-9<>/.!,?\s]+', '', tweet)

#Detect puncutation repetition

tweet = re.sub('(([!])\\2+)', '! <REPEAT> ', tweet)

tweet = re.sub('(([?])\\2+)', '? <REPEAT> ', tweet)

tweet = re.sub('(([.])\\2+)', '. <REPEAT> ', tweet)

#Remove hashtags

tweet = re.sub(r'#([^\s]+)', r'<HASHTAG> \1', tweet)

#Detect word elongation (e.g. heyyyyyy)

tweet = re.sub(r'(.)\1{2,}\b', r'\1 <ELONG> ', tweet)

tweet = re.sub(r'(.)\1{2,}', r'\1)', tweet)

#Expand english contractions

tweet = re.sub(r"'ll", " will", tweet)

tweet = re.sub(r"'s", " is", tweet)

tweet = re.sub(r"'d", " d", tweet) # Would/Had ambiguity

tweet = re.sub(r"'re", " are", tweet)

tweet = re.sub(r"didn't", "did not", tweet)

tweet = re.sub(r"couldn't", "could not", tweet)

tweet = re.sub(r"can't", "cannot", tweet)

tweet = re.sub(r"doesn't", "does not", tweet)

tweet = re.sub(r"don't", "do not", tweet)

tweet = re.sub(r"hasn't", "has not", tweet)

tweet = re.sub(r"'ve", " have", tweet)

tweet = re.sub(r"shouldn't", "should not", tweet)

tweet = re.sub(r"wasn't", "was not", tweet)

tweet = re.sub(r"weren't", "were not", tweet)

#Remove extra spaces

tweet = re.sub('[\s]+', ' ', tweet)

#Lower case

tweet = tweet.lower()

return tweetLet’s use train_test_split to split our data into training and testing data while applying our preprocess function.

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

train_data, test_data = train_test_split(data, train_size = 0.8, random_state = 42)

sentiment = np.array(data['sentiment'])

tweets = np.array(data['tweet'].apply(preprocess_tweets))

sentiment_train = np.array(train_data['sentiment'])

tweets_train = np.array(train_data['tweet'].apply(preprocess_tweets))

sentiment_test = np.array(test_data['sentiment'])

tweets_test = np.array(test_data['tweet'].apply(preprocess_tweets))We’ll build a word2count dictionary that will have a key entry for each word found in the data and a value corresponding to how many times that word was seen. Later, a reasonable threshold that included slightly more than 95% of word occurrences was chosen.

word2count = {}

for tweet in tweets:

for word in re.findall(r"[\w']+|[.,!?]", tweet):

if word not in word2count:

word2count[word] = 1

else:

word2count[word] += 1

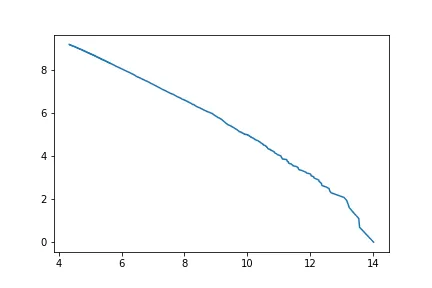

total_count = np.array(list(word2count.values()))

print(sum(total_count[total_count > 75]) / sum(total_count))0.9551287692699321Zipf’s Law is an empirical approximation which states that the second most frequent word in a language is used half as frequently as the first one, the third one, a third of the frequency of the first one and so on. Mathematically, Zipf’s Law can be defined as , where represents the frequency of the n-th most frequent word and is approximately 1. This relationship can be seen as a line in a log-log plot with the y-axis as log(count) and x-axis as log(rank) of words:

Thus, word frequency exponentially decreases and words that are rarely seen provide little to none information to our model and make it much more complex and sparse. Therefore, only relatively frequent words are included while still holding most of the information.

Vectorizing

We’ll build a bag of words, in which each tweet will become a vector of length n, where n is the number of words in our dictionary, and the values of this vector correspond to how many times that word is seen in that tweet. This approach, however, has a huge disadvantage: very frequent words (such as the and a) will almost always have the highest counts, while actually holding little information. The TF-IDF (term frequency times inverse document frequency) approach tackles this issue by using a different count value: we’ll use a simple approach and multiply the text (tweet) frequency of a word by , where is the number of documents and is the number of documents which contain the word. Thus, the transformed count value will indicate which words stand out as most unique and defining on each tweet.

from sklearn.feature_extraction.text import TfidfVectorizer

vectorizer = TfidfVectorizer(min_df = 75)

vectorizer.fit(tweets)

tweets_bow_train = vectorizer.transform(tweets_train)

tweets_bow_test = vectorizer.transform(tweets_test)Next, a logistic regression will be the model of choice to classify the data. As the model will receive a huge input vector while having to output a single value, it’s reasonable that the weights should be relatively sparse, that is, many words should have little to no influence on the output. Thus, we’ll use L1 penalty to ensure sparsity in the model. The C parameter is the inverse of regularization strength, that is, lower C values result in a stronger regularization and sparser solutions. We’ll try three different C values. A fourth model with L2 penalty and C = 1 (default value) will be fit for comparison.

from sklearn.linear_model import LogisticRegression

regressor1 = LogisticRegression(C = 1, penalty = 'l1', solver = 'liblinear',

multi_class = 'ovr', random_state = 42)

regressor1.fit(tweets_bow_train_idf, sentiment_train)

regressor2 = LogisticRegression(C = 0.5, penalty = 'l1', solver = 'liblinear',

multi_class = 'ovr', random_state = 42)

regressor2.fit(tweets_bow_train_idf, sentiment_train)

regressor3 = LogisticRegression(C = 0.1, penalty = 'l1', solver = 'liblinear',

multi_class = 'ovr', random_state = 42)

regressor3.fit(tweets_bow_train_idf, sentiment_train)

regressor4 = LogisticRegression(solver = 'liblinear', multi_class = 'ovr',

random_state = 42)

regressor4.fit(tweets_bow_train_idf, sentiment_train)We’ll use area under the curve (AUC) and F1-score to measure models’ performance.

from sklearn.metrics import roc_auc_score, f1_score

pred1 = regressor1.predict(tweets_bow_test)

pos_prob1 = regressor1.predict_proba(tweets_bow_test)[:, 1]

auc1 = roc_auc_score(sentiment_test, pos_prob1)

f11 = f1_score(sentiment_test, pred1, pos_label=4)

pred2 = regressor2.predict(tweets_bow_test)

pos_prob2 = regressor2.predict_proba(tweets_bow_test)[:, 1]

auc2 = roc_auc_score(sentiment_test, pos_prob2)

f12 = f1_score(sentiment_test, pred2, pos_label=4)

pred3 = regressor3.predict(tweets_bow_test)

pos_prob3 = regressor3.predict_proba(tweets_bow_test)[:, 1]

auc3 = roc_auc_score(sentiment_test, pos_prob3)

f13 = f1_score(sentiment_test, pred3, pos_label=4)

pred4 = regressor4.predict(tweets_bow_test)

pos_prob4 = regressor4.predict_proba(tweets_bow_test)[:, 1]

auc4 = roc_auc_score(sentiment_test, pos_prob4)

f14 = f1_score(sentiment_test, pred4, pos_label=4)Model 1:

AUC: 0.8782442518806748

F1: 0.8017438980490371

Model 2:

AUC: 0.878181401427863

F1: 0.8021068750172958

Model 3:

AUC: 0.8724711782629141

F1: 0.7978355389550899

Model 4:

AUC: 0.878032003703207

F1: 0.8012445320682644Model 1 is the best one AUC-wise, while model 2 is the best one according to F1 score. Let’s see the sparsity on each model:

sparsity1 = np.mean(regressor1.coef_.ravel() == 0) * 100

sparsity2 = np.mean(regressor2.coef_.ravel() == 0) * 100

sparsity3 = np.mean(regressor3.coef_.ravel() == 0) * 100

sparsity4 = np.mean(regressor4.coef_.ravel() == 0) * 100

print('Sparsity with L1 and C = 1: %.2f%%' % sparsity1)

print('Sparsity with L1 and C = 0.5: %.2f%%' % sparsity2)

print('Sparsity with L1 and C = 0.1: %.2f%%' % sparsity3)

print('Sparsity with L2 and C = 1: %.2f%%' % sparsity4)Sparsity with L1 and C = 1: 15.51%

Sparsity with L1 and C = 0.5: 29.29%

Sparsity with L1 and C = 0.1: 72.18%

Sparsity with L2 and C = 1: 0.00%It’s quite amazing that even with 72.18% of coefficients set to 0, model 3 was still able to achieve a performance almost identical to much more complex models. Also, sparsity raises model performance and makes it simpler, as the L2 model with no sparsity is much more complex and performs a bit worse according to both metrics.

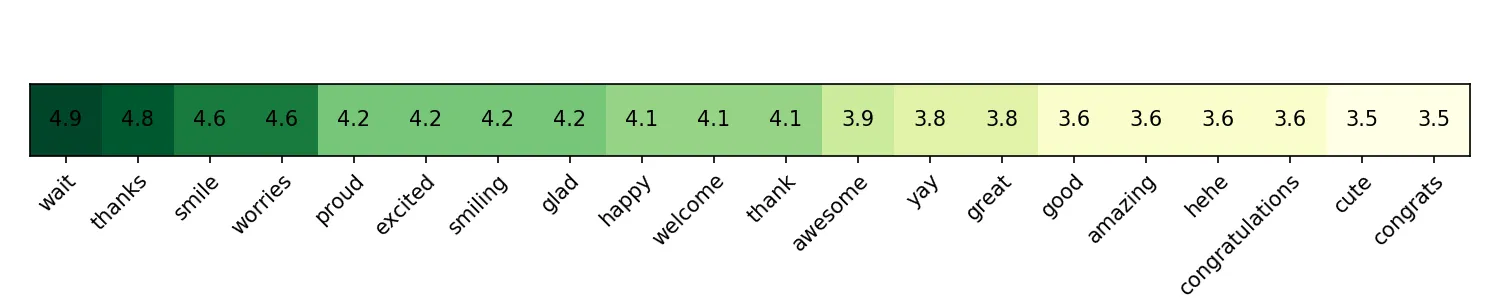

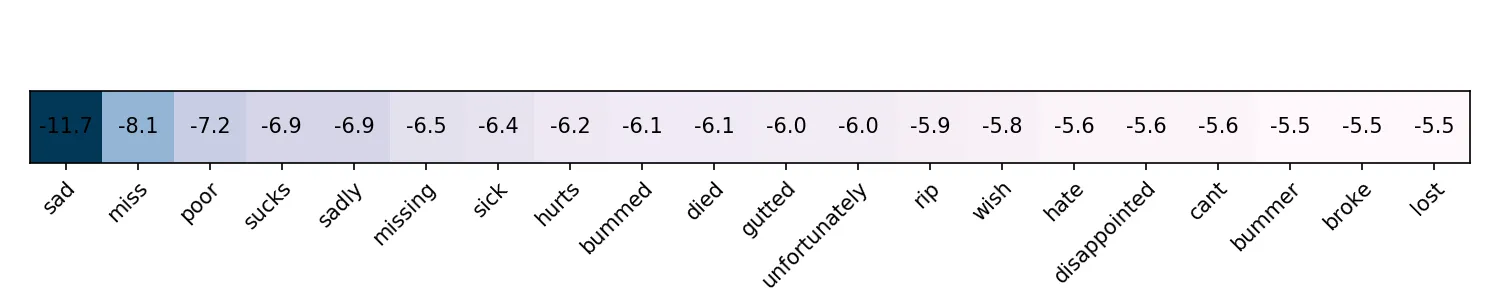

Interpreting the model

Let’s see which words have the biggest contribution for both positive and negative sentiment. The third model will be used as it’s more sparse and allows for better interpretation.

coefs = np.array(regressor3.coef_.ravel())

sorting = coefs.argsort()

high_coefs = []

high_words = []

for i in range(-1, -21, -1):

high_coefs.append(coefs[sorting[i]])

temp = np.zeros(coefs.shape[0])

temp[sorting[i]] = 1

high_words.append(vectorizer.inverse_transform(temp)[0][0])

low_coefs = []

low_words = []

for i in range(20):

low_coefs.append(coefs[sorting[i]])

temp = np.zeros(coefs.shape[0])

temp[sorting[i]] = 1

low_words.append(vectorizer.inverse_transform(temp)[0][0])

high_coefs = [high_coefs]

low_coefs = [low_coefs]

high_coefs = np.round(high_coefs, 1)

low_coefs = np.round(low_coefs, 1)

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize = (10, 2))

im = ax.imshow(high_coefs, cmap = 'YlGn')

ax.set_xticks(np.arange(len(high_words)))

ax.set_xticklabels(list(high_words))

plt.setp(ax.get_xticklabels(), rotation=45, ha="right",

rotation_mode="anchor")

ax.axes.get_yaxis().set_visible(False)

for i in range(20):

text = ax.text(i, 0, high_coefs[0][i],

ha="center", va="center", color="black")

fig.tight_layout()

plt.savefig('highest_heatmap.png', dpi = 150)

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize = (10, 2))

im = ax.imshow(low_coefs, cmap = 'PuBu_r')

ax.set_xticks(np.arange(len(low_words)))

ax.set_xticklabels(list(low_words))

plt.setp(ax.get_xticklabels(), rotation=45, ha="right",

rotation_mode="anchor")

ax.axes.get_yaxis().set_visible(False)

for i in range(20):

text = ax.text(i, 0, low_coefs[0][i],

ha="center", va="center", color="black")

fig.tight_layout()

plt.savefig('lowest_heatmap.png', dpi = 150)

Many words are quite predictable. However, worries stands out among positive ones. Still, we can think that tweets containing worries talk about it lightly, while the word worried might have a negative connotation instead.

Let’s take a look at the 10 most correct positives:

pos_indices = sentiment_test == 4

pos_predicted = pos_prob1 > 0.5

true_positives = pos_indices & pos_predicted

true_positives_rank = np.argsort(pos_prob1[true_positives])

print(tweets_test[true_positives][true_positives_rank[range(-1, -11, -1)]])['<user> <url> <elong> you look great. and happy. smiling is good. haha. i love your smile.'

'<user> glad it makes you happy. smile '

'<user> welcome and thank you for the followfriday! '

'<user> <user> happy birthday. we love you! thank you '

'<user> yay! <repeat> thanks for the followfriday love! <repeat> '

'<user> welcome home! im glad you had a great time, thanks for the amazing updates '

'<user> im glad you enjoy! thanks!'

'<user> yay <elong> ! thank you! youre awesome! <repeat> '

'<user> your welcome! thanks for sharing the great quote. '

'waves good morning and smiles her best smile! <url> ']Top 10 true negatives:

neg_indices = sentiment_test == 0

neg_predicted = pos_prob1 <= 0.5

true_negatives = neg_indices & neg_predicted

true_negatives_rank = np.argsort(pos_prob1[true_negatives])

print(tweets_test[true_negatives][true_negatives_rank[range(10)]])['is sad. i miss u . <repeat> '

'i cant believe farrah fawcett died! so sad '

'rip <allcaps> farrah fawcett! this is so sad '

'so sad to hear farrah fawcett died '

'<user> i had boatloads of sharpies and i didnt go! <repeat> sad sad sad sad so very sad. '

' sad awkwardness' 'im sad. <repeat> i miss my <user> '

'sad i dont know why i sad ' 'sad sorrow weary disappointed '

'i hate i missed roo im so sad ']Top 10 false negatives:

pos_indices = sentiment_test == 4

neg_predicted = pos_prob1 <= 0.5

false_negatives = pos_indices & neg_predicted

false_negatives_rank = np.argsort(pos_prob1[false_negatives])

print(tweets_test[false_negatives][false_negatives_rank[range(10)]])['<user> <allcaps> dont be sad. it doesnt make me sad '

'im not sad anymore ' '<user> that is sad! '

'dubsteppin. miss my lovies. '

'saw quotdrag me to hellquot sadly it scared me <elong> hate the ending. '

'btw, bye <user> dang! wish u went along wit them. <repeat> sad sad.'

'the saddest person is texting me telling me about how sad my life is and is getting nothing right, now shes sad '

'<user> poor girl, the fever is horrible! i hate it! get well soon bama! '

'<user> your sad ' '<user> coucou miss ']Top 10 false positives:

neg_indices = sentiment_test == 0

pos_predicted = pos_prob1 > 0.5

false_positives = neg_indices & pos_predicted

false_positives_rank = np.argsort(pos_prob1[false_positives])

print(tweets_test[false_positives][false_positives_rank[range(-1, -11, -1)]])['<user> cool! thank you thank you '

'<user> hey say me something haha now that you in love, love, love 8 forget about me? haha luv ya and im so happy because u happy'

'<user> i love you,i love you,i love you youre the most beautiful and sweet girl ever.'

'thank you lol' 'wait for a wonderful day ' '<user> thank you'

'<user> thank you ' '<user> thank you lovie. ' '<user> thank you. '

'<user> thanks. ']Here we can see that most of these false positives/negatives probably are actually real negatives/positives. This suggests that there’s mislabeled data in the dataset. Moreover, this shows that the model has a good capacity of generalization, as it correctly classified mislabeled data.

This whole project shows that even a simple model, such as logistic regression, may have a very satisfactory performance with great generalization. Thus, it’s always best practice to begin with a simple model. On the following posts, I’ll use recurrent neural networks to tackle this task.